On the eve of D-Day, many men of the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers requested to see their parents prior to sailing, envisaging it could be for the last time. In contrast, their Commanding Officer threatened deserters with hanging during his final fire-eating speech, rousing them to display courage befitting the only Welsh unit taking part.

Those in the landing craft remember being cheered by each naval vessel they passed and waving back. Once beyond the Needles though, the rough sea forced most to retire to the cramped conditions below and pass the night. The craft was carrying nearly 300 men who had with them their webbing, packs, entrenching tools and weapons. One soldier, cramped and sea-sick recalls:

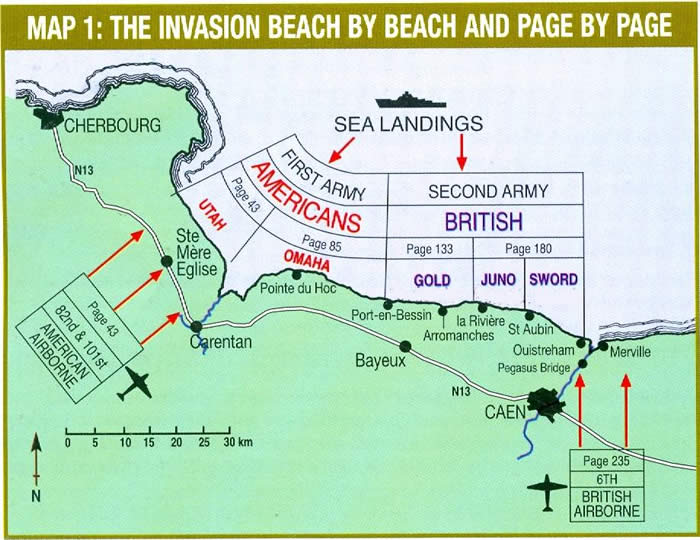

"The flat bottomed boats were all over the place. I have never felt so ill in all my life! As day broke, everyone came up on deck to see the Normandy coast hove into view. The cliff edges were wreathed in smoke and dust. To our far right much heavier fire seemed to be occurring on Omaha beach”.

Bill Speake describes how on leaving the craft he disappeared below water and managed to save himself only by pulling on the hawser rope to shore. He went under a number of times, his equipment dragging him down. His abiding memory of this incident is that of the 400 cigarettes he was carrying, only the 20 in a sealed tin in his helmet survived.

Islwyn Edmunds explains that they were expected to be a mobile force, so that as well as their 80lb packs they had to carry a collapsible bicycle:

Islwyn Edmunds explains that they were expected to be a mobile force, so that as well as their 80lb packs they had to carry a collapsible bicycle:

"Colonel Craddock led the way off down the narrow gangplank into the sea with a "follow me". He was wearing his soft hat and carrying a swordstick and pistol as personal weapons. He disappeared under the sea”.

Following a little way back, Islwyn was sure he was drowning as he went under a number of times, but was saved by Lance Corporal Melvyn Jones picking him up and thrusting him forward. Islwyn lost his bicycle and rifle but there was a dump of cycles just off the beach and he had to pick another. He replaced his rifle by picking up one of many ‘laying around on the beach’.

The Signals Officer, Sam Weaver, was festooned with all sorts of frequency codebooks in a haversack and held this over his head when entering the water. Colonel Craddock went first and Sam followed having a terrific struggle with water up to his chest and his waterproof anti-gas overtrousers filling up with water. Looking back he saw that not a single man had followed. One of his signallers, Higgins, said later, "We weren't going to follow you seeing you up to your neck!”

They had lost their direction boards and attached chalk had got soaked and was useless. The noise was terrific with shelling and mortaring still hitting the beach. Gradual progress was made as the Battalion moved along the sandy beach towards Le Hamel. In pockets, soldiers managed to get off the beach and struggled up the inland coastal road toward the Rendezvous Point at Buhot.

They had lost their direction boards and attached chalk had got soaked and was useless. The noise was terrific with shelling and mortaring still hitting the beach. Gradual progress was made as the Battalion moved along the sandy beach towards Le Hamel. In pockets, soldiers managed to get off the beach and struggled up the inland coastal road toward the Rendezvous Point at Buhot.

Sergeant Dick Philips, of 2nd South Wales Borderers HQ recalls:

"The sea was quite rough; we had these wide bows that made it worse. I was still going up and down from the voyage. During the landing we saw these young chaps with the Africa Star lying in the surf I thought these poor buggers; they have been through North Africa. They didn't even get up on the sands you know, and I thought that was terribly unfortunate. When we landed there was a lot of shelling and it was a bit hairy. As we were leaving the beach there was a chappie going up the bank and a shell exploded at his feet in the sand and we saw his body coming toward us in the air. Further on there was a farmhouse surrounded by a high wall with double gates, and an elderly lady was outside jumping up and down, clapping her hands at all these fellows leaving the beach.”

One Private remembers the menacing sniper fire as the terrain began to change:

"As we got into more dense countryside with hedges and where there were copses and trees, the tank commander asked us to go in front to scout out if there were any German 88mm guns around. Some places we had to stop when we came under sniper fire. Then the platoon officer had a couple of our own snipers sent forward to try and spot them. They were mainly up in trees. I don't think we felt frightened it was just the unexpected, not knowing what was in front of you”.

One of the Battalion’s objectives on the way to Vaux-sur-Aure was to capture the German Radio Direction Finding station near Pouligny. Captain Josh Wickert, firing from the hip in the lead Carrier, promptly knocked out the German post. The target gave some brief resistance, before the Germans set fire to it and abandoned it as the Company attacked.

One of the Battalion’s objectives on the way to Vaux-sur-Aure was to capture the German Radio Direction Finding station near Pouligny. Captain Josh Wickert, firing from the hip in the lead Carrier, promptly knocked out the German post. The target gave some brief resistance, before the Germans set fire to it and abandoned it as the Company attacked.

In the gathering darkness, the exploding ammunition from the RDF Station lit up the sky. Major Peter Martin, who was leading the forward party, was talking to a Forward Observation Officer in a tank. As the tank moved, it set off a mine in the road. Peter Martin caught the full blast in the stomach and was badly wounded. A stretcher carrying jeep immediately evacuated him. By 2350hrs the forward party were able to report the capture of the bridge at Vaux-sur-Aure.

The 2nd South Wales Borderers was the one unit of the whole British invasion force who advanced the furthest on D-Day. They had lost just four men; two by mortar fire on the way to Buhot, Sergeant Reynolds and Private Price, and two from sniper fire, Privates Massey and Parr. Ivor Parr was killed in the locality of Magny and initially a local French family buried his body. Later he was re-interred by locals at the church of Magny, where his grave remains today. Reynolds, Massey and Price are buried at Bayeux. The Battalion also had about twenty other men wounded.